Book Review - 'Wasted' by Ankur Bisen

On our failed tryst with sanitation and what we can do from here

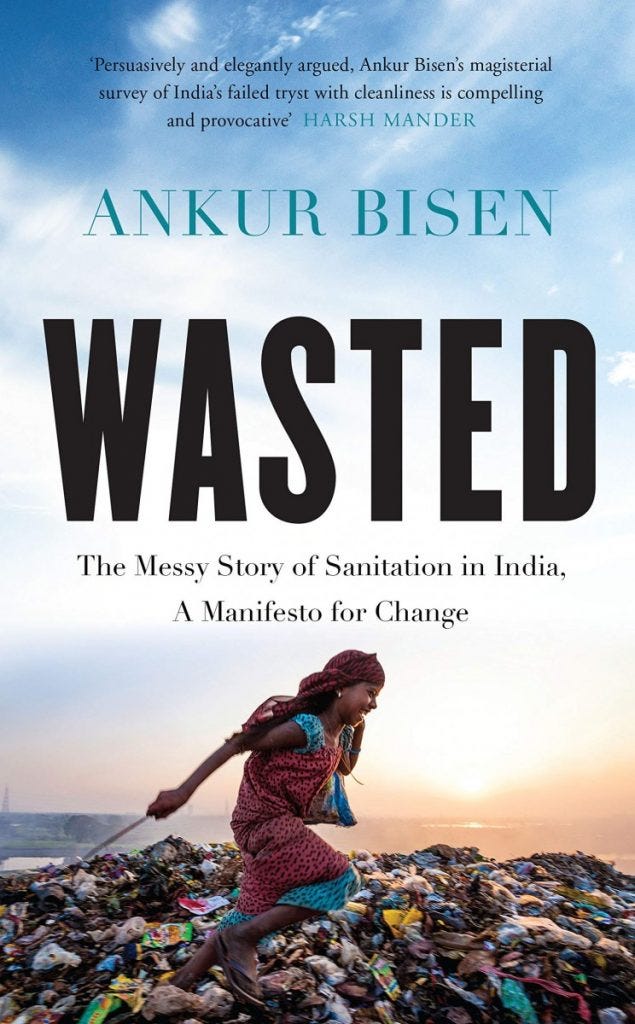

While I celebrated the success of Chandrayaan 3, I was leafing through Ankur Bisen’s mammoth account of all that is wrong with waste management in India. Our country’s idiosyncrasy is best described by the state of our space program and sanitation. One is a matter of pride and is world class, the other is stuck in the dark ages.

This is also topic that shapes my day to day existence because my wife works in the waste management sector and we live a life that is considered a bit odd in present day Bangalore (but really shouldn’t be). For instance we compost all our waste at home, we do 1 or 2 Zomato/Swiggy orders in a year, loathe quick commerce and don’t shop from supermarkets to reduce the amount of waste we generate. (Kirana stores ftw!)

While the above might seem extreme (as it did to me after I moved in with my wife), what Bisen’s book made me realise is that taking control of the waste I generated was the only way I could be sure that I was not loading the landfills outside Bangalore. Data around waste is hazy and contestable. The percentage of waste that is scientifically managed is anywhere between 70% to 30% depending on who you ask. Going by the number of landfills and mixed waste strewn around the country however, the true number is likely to be on the lower end. The lack of consistent data itself is a red flag.

Bisen breaks down the book into 8 chapters but the book is largely about people, organisations, urban planning, informality, collection and disposal. Each chapter is a deep dive into the malaise affecting that particular aspect of waste management in India. He gives a plethora of examples to support his claims and provides some ideas that suggest ways out of the mess that is sanitation in India.

I’ve structured this post on the basis of the insights I took away from the book rather than the flow of the book. There are a lot of lessons from this book that extend to sectors beyond waste because waste is an intersection of public behaviour, organisation design, urban planning, manufacturing technology, leadership and scale. Mastering the issue of waste is in my opinion a pre-requisite to calling ourself a developed nation and confronting the problem is also confronting some of our most uncomfortable tendencies as a nation.

Insight 1 - Indian society needs to reset its relationship with waste and waste workers

There’s a section in the book which describe the average day in a middle class household. There’s a house help who come home, does the chores and at the end of her day’s work carries the waste generated the previous day in a polythene bag and chucks it in an open patch of land on the way to the next home. The waste is typically unsegregated and is picked up by the municipality later, often after the bag has been mauled by a dog and the contents scattered on the road. This is a common scene in cities like Bangalore and while some housing societies mandate that the waste be segregated, it is still left to the workers in the building to come pick it up and in most cases, the waste left outside the front door, isn’t segregated.

Why is it that we outsource the work of dealing with waste? How are we OK as a society with millions of us nonchalantly littering on our streets? Why is it that most Indian households can’t bother to do the basic work of segregating waste as dry and wet? Bisen argues that it is because there is someone to pick it up regardless of the state of the waste. As a society we are OK with some people dealing with unsegregated waste working with little to no protective equipment because it is convenient and more importantly, free. We have internalised paying for water, electricity and gas but not for dealing with waste which has its own cost of disposal. This ‘free’ service is kept possible because we have people willing to work for astonishingly low wages and a society that turns a blind eye to their working conditions. Waste workers are ‘invisible’ and both society and the workers are unfortunately ok with this status quo creating an eerie equilibrium that benefits neither. There is also a strong correlation with this status quo and the caste system and the book made me look at that correlation more deeply. There has to be a sense of shame and outrage that we treat a section of our population this way.

Insight 2 - Social contracts that are enforced are fundamental to driving good behaviour.

Fundamental to a well functioning society is social contracts. We cannot break a red signal because it could endanger someone else and are fined if we are caught doing so. So why is it that signals are broken with impunity in India? Because people know they can get away with it 9 times out of 10 and hence the threat isn’t ‘real’. Littering is no different. Our understaffed traffic police force is akin to our understaffed waste management workforce. Without any power to punish transgressions, waste workers are powerless and are are left to pick up the remnants of our abhorrent behaviour.

On top of this, contractors hired to pick up this waste are incentivised by weight, hence they go to any length to pick up waste and dump it in a landfill, further incentivising bad disposal behaviour creating a vicious circle. To break this circle requires political will and sponsorship. In the absence of the will to enforce this social contract, we default to behaviours that are inconsistent with the complexity and scale of waste we generate as a country. In other words, we cannot continue behaving the way we do with our waste unless we are ok with the public health complications it will eventually lead to. There are many examples of us being able to execute social contracts well. Wearing masks during the peak of COVID is an example. We need the same will and rigour with waste. This will cost money of course, but there is no other way around this. We live in a kind of waste anarchy today where anything goes and without the state machinery behind enforcing this contract, it is bound to fail.

Insight 3 - Our municipal bodies are incapable of handling the challenge that our waste presents, on their own.

The municipal bodies in India have little capability and capacity to deal with the quantum of waste generated in a scientific way. Bisen dives into the cause of this and attributes it to the lack of financial and administrative autonomy of municipal bodies. He cites the example of the perennially cash strapped BBMP in Bengaluru, and contrasts it with municipal bodies in clean nations. The role of the mayor in India is merely that of serving a political master and hence it is very often the Chief Minister who is trying to douse a waste crisis that emerges every few years. Why is this so, he questions and how can municipalities ever equip themselves with the technical and operational expertise needed if they continue to operate the way they do today. Bisen argues for a central policy (which exists today) with execution bifurcated into two. Waste collection being under the the ambit of local bodies and industrialisation of waste disposal.

Insight 4 - Informality is the enemy of building capacity

This was one of my favourite insights from the book as we have come to take informality and a lack of urban planning for granted in India. However, there is an inextricable link between the lack of the planning and informal ways of living which then leads to waste generation in an unplanned fashion. Waste generation in an unplanned fashion means waste collection cannot keep up and informal collection methods are born as a consequence. This informal collection system feeds an informal processing system, which inevitably means irresponsible disposal. There is a flywheel of informality that can be argued is a central reason for our waste woes.

But stopping this flywheel is hard. How does one ask for instance, the subzi mandi that pops up on a road on weekends to suddenly stop. Where does one move them? Or the street vendors in every corner of the city. If the vote bank is largely involved in informal work, then how does one conjure the political will to make changes? There are no easy answers but slowly converting informal businesses to formal ones is essential to also manage the remnants of those businesses, Bisen argues.

Insight 5 - Waste management can contribute a sizeable amount to our GDP

The waste urban India generates is as complex as any other country’s but our means to deal with it is a century behind in its ability. Creating the means is a lucrative opportunity. This is illustrated by the size of our waste management market. India generates 12% of the world’s waste but we’re not making the most of it. Industrialising waste management has a huge upside and while there has been effort in the policy making, the execution leaves much to be desired. Some estimates peg the potential size of this market to be $14 Billion USD in 2025. The EV market is estimated to be about $7 billion at the same time.

Hoping with Reason

While Wasted is a great overview of everything that is wrong, it doesn’t offer a coherent way out of the crisis. Instead it drops hints in various parts of the book. Given the complexity of the problem, maybe a coherent solution warrants a book of its own. The book offers hope by showing success stories within and outside India. It also makes one thing clear that, waste in India is as much a societal malaise as it is bureaucratic. Which means a large chunk of the problem lies with us, the people, which also consequently means a large chunk of the solution lies with us. While the bureaucracy sorts its mess out, literally, this is one problem where civil society can play a large role. Communities that organise themselves well can make a big dent. In the absence of strong social contracts enforced by the state, communities can create it by calling out those in violation of norms in their neighbourhood. This requires will and effort of course but in the absence of this, we are staring down a bleak future with regards to sanitation. Our lakes will continue to kill fish and our neighbourhoods will continue to reek of garbage.

The other big bureaucratic chunk of the problem requires many fixes but any solution that has promise will require an industrialisation push from the government like never done before. A PLI like scheme dedicated to waste management inviting companies to set up state of the art facilities might be a bright start. Maybe these plants can be run by a central body instead of municipal bodies. These plants will have to be fed segregated waste by the local bodies. This can be run profitably and this inherent viability offers hope for a cleaner future as long as society is willing to pay for this service. Leadership that can convince the public of doing this is crucial in making this happen. Much like agriculture we need to wake up to the necessity of mechanisation of waste management and that cleanliness doesn’t come free.

Great summary Shreyas!!